Making Peace in Kindergarten: Social and Emotional Growth for All Learners (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Frances Rust, Voices Executive Editor

In his seminal study of schools and teaching, Life in Classrooms, Philip Jackson wrote,

"Three important facts a child must learn to deal with in a classroom involve crowds, praise, and power. First, the student has to learn to live amongst a crowd. Many of the classroom activities will involve being in a group or in the presence of a group. A student’s quality of life can depend greatly on how well he works amongst a crowd" (1968, 9).

In this article, Holly Dixon examines this fact of learning to live in a crowd—a hard concept for children just emerging from an egocentric focus in Piaget’s preoperational stage. Using puppets, the peace corner, and the marshmallow challenge, Holly explores how a group of kindergarten students in a Philadelphia public school learn to share resources, gain the ability to conform to a schedule, and build the resilience essential for taking turns. Holly’s study was undertaken as part of her master’s program. Her insights about creating an environment that enables children to become problem solvers informed her own practice—something that teacher research invariably does. What was completely unexpected was how the children’s embrace of peacemaking inspired other teachers and the school principal to carry the peace corner forward as a core practice of the school.

As a master’s student reflecting on my elementary school education, I realized that the academic knowledge that I gained each year seemed to have been related to the social and emotional feel of the classroom. I felt successful as a student when I felt cared for as a human being. Thinking back on my experience as a student inspired me to try to become a teacher who thinks about all facets of my students’ lives. It also led to my research question: “How can teachers support children’s social and emotional learning?”

My first student teaching placement took place in a second grade classroom in which the teacher had established a positive classroom culture that seemed to embrace the social and emotional needs of her students. A key component of the classroom was the “peace corner,” a place where students could go to address social conflicts. The teacher told me she created the space to demonstrate her commitment to making students feel safe and secure, a place where each student could be seen as a “whole child.” Though I had observed some children solve problems there, I wondered whether the corner was effective for every child in the classroom.

I began my inquiry by watching two students work out a problem in the peace corner. I noticed that they displayed different ways of engaging in conflict resolution: Felix was attempting to make eye contact and use “I” statements, while Charlie, scanning the room, seemed disengaged and appeared to have difficulty finding the words to communicate his feelings. There could have been many reasons why Charlie seemed disengaged. Maybe his ability to recognize emotions in himself and others was less developed than his partner’s, or perhaps he was engaged but absorbed the information without making eye contact. There were so many possibilities to explain what I was seeing that I wondered what I might do to make it effective and meaningful for all students. I decided to focus on helping students develop the vocabulary for describing their feelings and the essential skills for exchanging ideas.

Review of the literature

My inquiry was primarily guided by research on teacher actions that promote deep learning by honoring the whole child in caring and equitable learning environments. I focused on research related to children’s need for social and emotional well-being, the value of considering children’s multiple intelligences and diverse learning styles, and practices that mitigate issues associated with competition. My interest in supporting the personhood of my students—their uniqueness as individuals—is supported by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see McLeod 2016). Maslow prioritized needs ascending from physiological needs through psychological ones, ending with self-actualization. The idea is that humans are optimally motivated relative to the level at which their needs are met. The implications of this work suggest that meeting students’ basic needs for security and comfort are essential if optimal learning is the desired outcome.

As I tried to find ways to support a more learner-centered environment, Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences was helpful. Gardner holds that rather than being a singular construct, intelligence is a blend of eight intellectual capacities and associated mental processes: visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, and naturalistic. Gardner claims individuals have varying levels of strength in each of these intelligences and in the way they process information. Like Maslow, Gardner had critics of his theory; however, it is generally believed that learners are complex and diverse in their abilities and aptitudes. As such, many educators have drawn from Gardner’s theory to shape learning environments supportive of a wide range of strengths and abilities.

Although multiple intelligences are often seen as interchangeable with learning styles—sometimes conceptualized as learner types, such as auditory, visual, and kinesthetic (Grist 2009)—the two are distinct and have different implications for classroom use. Prashnig (2005) makes the distinction, writing: “Learning styles can be defined as the way people prefer to concentrate on, store, and remember new and/or difficult information. Multiple intelligences is a theoretical framework for defining/understanding/assessing/developing people’s different intelligence factors” (8).

My approach to setting up an environment in which equity and caring could reign was informed by Edwards’s (1993) Reggio Emilia-influenced frame for creating an “educational caring space” and Kohn’s (1987) work on competition. Kohn argues against comparing children’s performance with that of siblings and classmates. He suggests that acceptance should never be based on a child’s performance and holds that it is especially important that teachers be aware of the powerful modeling that they provide.

Developing a climate for peace

Questions about the peace corner in my first placement—how it was set up, the way children used it, and the impact it might have on children’s interactions with one another—stayed with me as I began my second placement, where I worked in a kindergarten class at a small, urban, Title 1 school in Philadelphia. The majority of the 14 boys and 14 girls in the class lived close to the school. Twenty were African American, six were White, and two were Asian. One of the 28 students was an English language learner.

A typical day began with an all school meeting that included announcements and recitations of the Pledge of Allegiance and school promise. Afterward, once the children arrived in the classroom, the kindergartners would put away their belongings, go to their seats, and write in their journals. The arrangement of the desks—grouped together to create five different teams—provided opportunities for positive student interaction as well as potential for conflict. Typically, the most difficult part of the morning occurred during this busy transition from the schoolwide meeting to the classroom as the children attempted to negotiate each other’s personal space. Negotiating personal space was a similar catalyst for conflict when the children were standing in line, sitting on the carpet, transitioning in and out of the classroom (e.g., group bathroom trips, hand washing, retrieving items from cubbies), having lunch, and, most frequently, playing at recess. These conflicts frequently resulted in children resorting to name-calling, shouting, and hitting. Generally, at these moments a crowd of students would form and seek an adult to deal with the source of their problem. My classroom mentor and I were bombarded with students’ reports of social injustices. Rarely were these reports preceded by children’s attempts to find a solution on their own.

While helping students resolve conflict, I began to realize they might benefit from learning how to properly identify their feelings and communicate them respectfully. It was January, and I had heard only one of my students use words other than “mad” or “sad” to articulate their emotions. Determined to empower my students, I planned a thematic and integrated unit (Tomlinson & McTighe 2006) based on the social and emotional skills I thought my students needed to develop in order to become more independent problem solvers in and out of the classroom. A major part of my planning was finding ways to incorporate each of three sensory learning styles (auditory, visual, and kinesthetic) into as many of my lessons as possible, with the ultimate goal of empowering my students to identify and communicate their own feelings. I knew that in order for them to develop these new skills, I needed to use a variety of ways to enable them to practice the new communication skills.

I had laid significant groundwork in the months prior to implementation of the unit. Every week, I introduced my students to emotional vocabulary. Often, I had to provide the word’s meaning and an example of its use because words such as embarrassed, nervous, lonely, hurt, frustrated, annoyed, happy, scared, angry were new to many of the children. I presented a new “feelings word” each day, asked what they thought the word might mean, and encouraged them to talk about a time they experienced that feeling themselves. Throughout the week, I used each new word frequently so that the students became familiar with hearing it. I kept anecdotal records noting when students used the new emotional vocabulary.

The following is an example of children using more specific emotional vocabulary:

Christopher: This weekend I thought of another feelings word that’s like mad and angry.

Teacher: Oh? What word did you think of?

Christopher: Disappointed!

Teacher: That’s a great feelings word! Were you feeling disappointed this weekend?

Christopher: No. I just thought of the word and thought, I gotta tell my teacher this week!

After students began to use the new vocabulary for themselves, I tried to arrange opportunities for them to interpret others’ feelings. I created two original puppet characters, Holly Owl and Bunny, who helped the children discuss conflict and the multiple perspectives accompanying conflict. I introduced one character at a time as the puppets sought the children’s help in their own puppet kindergarten drama. The first narrative involved a lunchroom scenario because it was similar to their day-to-day struggles during lunchtime.

Holly Owl is livid when Bunny spills milk all over her feathers at lunchtime. Holly is so upset that she flutters off in a rage about being sticky—she has revenge on the brain! Not knowing what to do, she asks for advice from the kindergartners on how to approach Bunny. After Holly Owl thanks the class for the tips and says “Goodbye,” Bunny appears and tells her side of the story—she reached over to get her fork and her long, floppy ear knocked over her milk, causing it to soak Holly Owl. Bunny felt horrible. When she looked up, Holly Owl was fuming; steam was coming out of her ears! There is no way Bunny is going to apologize to such an angry owl. But now, time has passed and they haven’t talked to each other all afternoon. Bunny is scared that Holly Owl will absolutely hate her forever. She tells the children, “I’m so scared. I just don’t know what to do!”

We decided to brainstorm for Holly Owl and Bunny. Together, the class wrote letters to both puppets, sharing advice on resolving the conflicts. After all the letters were complete, I took them home to read to Holly Owl and Bunny.

The following day, I brought the puppets back to thank the children for all their helpful advice. Holly and Bunny then resolved their conflict for the kindergartners, modeling the advice the children had written. This first use of puppets to resolve conflict became a common reference point for the children, and the puppets appeared in a variety of contexts throughout the semester.

Everyone needs a peace puppet

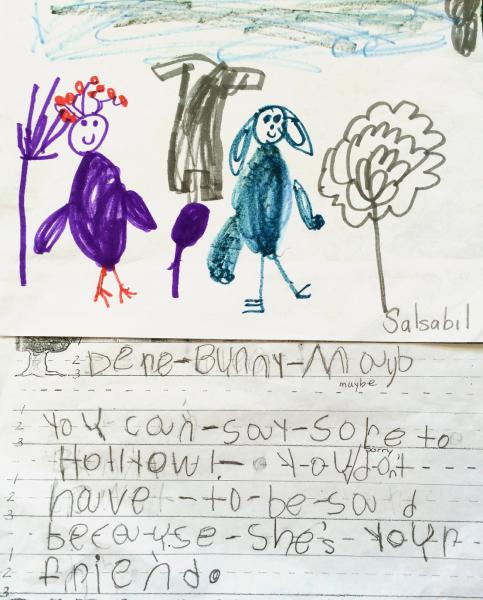

The children took such interest in the puppets that they asked if they could create their own. As a class, we brainstormed how to make puppets, writing down ideas for materials as well as what purpose our puppets  would serve. We voted and decided to name them “peace puppets.” Students brainstormed in pairs to create character descriptions, settings, and a point of conflict for their characters. Once a scenario was established, students wrote about ways the puppets could approach their problem to find a solution. This seemed to work as a “warm up” or context builder for making the puppets.

would serve. We voted and decided to name them “peace puppets.” Students brainstormed in pairs to create character descriptions, settings, and a point of conflict for their characters. Once a scenario was established, students wrote about ways the puppets could approach their problem to find a solution. This seemed to work as a “warm up” or context builder for making the puppets.

Puppets were created using wooden spoons, fabric, rubber bands, paper, yarn, colored pencils, and hot glue. When it came time to use the peace puppets, I noticed that those children usually least inclined to speak in social contexts came to life with intensity. It was as if the puppets gave them a voice that they were not yet ready to use on their own. Each student accepted their own puppet’s unique qualities and each other’s by taking special care of the toys during play and displaying pride in them. Their actions with the puppets seemed to say, “I accept myself and I accept others.” After a while, the peace puppet theater became an important supplemental activity and place for students to exercise their ability to problem solve and care for one another.

Introducing the peace corner

The planning and collection of samples of student work, anecdotal notes on students’ use of feelings words, my mentor’s observational notes, daily observations, and my own reflection journal—all helped me move toward my ultimate goal of creating a full unit to help my students develop the social and emotional skills that would equip them to be effective problem solvers. Developing a peace corner was the obvious next step. Inspired by the model that I had observed during my first student teaching placement, I hoped to implement an enhanced version in my classroom.

I located our peace corner in a loft space in the back of the classroom that was used for dramatic play, because of the privacy it afforded. I furnished the loft space with a table and chairs for student conversations. On the table, I placed a book of student drawings and words describing a problem- solving scenario as well as a five- minute sand timer to help regulate the pace of conversations. To track student attendance, I created a sign-in sheet attached to a clipboard with a pencil. In addition to these items, I posted anchor charts taken from our lessons and brainstorming sessions. On the loft’s wall, I set up a feelings wheel. This arrangement seemed to be appropriate for creating a place that had the potential to support high quality social and emotional learning.

Practicing peacemaking

.jpg) Within a month of its introduction, the peace corner had been used by all the students in the class. In the first 10 days alone, 71 percent of the class went there in pairs to solve problems. Data collected on children’s usage suggests that the peace corner was especially effective for students like Alicia, who used the peace corner eight times with six different partners.

Within a month of its introduction, the peace corner had been used by all the students in the class. In the first 10 days alone, 71 percent of the class went there in pairs to solve problems. Data collected on children’s usage suggests that the peace corner was especially effective for students like Alicia, who used the peace corner eight times with six different partners.

I noted that during these first 10 days, six pairs of students left the peace corner seeming to feel validated and with their issues resolved. Students, often smiling, excitedly reported to me after their peacemaking sessions, debriefing me on their successes and challenges working through conflict. They then went on to work collaboratively during centers, writer’s workshop, and math.

The peace corner supported positive change in the class in several ways. First, the students’ dependency on me as an authority to stop conflict shifted. They began to ask for time to solve their problems themselves instead of asking me to solve problems for them. This made my teaching more effective because the time I spent on managing peer relationships dramatically decreased, enabling me to channel my focus toward learning objectives while spending more time supporting students’ individual academic needs. Over the course of the two-week data collection period, I only found it necessary to help mediate twice, and both times it was because the students had already spent the maximum five-minute period discussing their problems independently.

Talking and sharing as problem solvers

Drawing on the progress my students had made with social and emotional problem solving, and following Alfie Kohn’s work regarding the dangers of competition, I wanted to create an opportunity for my students to explore the essential elements of effective teamwork. The Marshmallow Challenge (Wujec 2015)—a timed group activity using limited materials to build a freestanding tower topped with a marshmallow—seemed an appropriate vehicle for this. Although the challenge can be framed as a competition, I emphasized active listening and communication. I had faith in my students’ ability to infer the larger purpose of the activity from my instructions: “The goal is to use teamwork to make your towers as tall as you can in 18 minutes.” The implied purpose of the activity was for the children to work together as a team using listening skills, positive communication, persistence, encouragement, and reflection to identify what each team could work on to become more productive as a group.

In this phase of my inquiry, my focus was on identifying ways my kindergarten students used listening and communication skills for team-building.

For this activity, seven-member teams are given 18 minutes to build the tallest freestanding tower they can, finishing with the marshmallow sitting atop the tower. They are allotted the following list of materials:

- 1 box raw spaghetti

- 1 bag of marshmallows

- 1 yard of string each

- 7 scissors

- 1 yard of masking tape each

- 1 timer

As they worked, I listened to the team members interact:

Sophie: Hurry, guys! We are gonna lose! We only have 10 more minutes!

Amir: Guys! This is not a competition! No one wins. No one loses.

On completion of the challenge, I asked teams to reflect on their process, naming what helped their team and what hurt their team’s performance. Below is a discussion from the group reflection:

Teacher: What were some of the challenges your team faced today?

Mary: When we were trying to build our tower, I noticed that Jaylan couldn’t get the tower to stand up because she wasn’t believing in herself.

Teacher: Jaylan, what do you think about what Mary said?

Jaylan: She is right [smiles]. I was feeling very frustrated because I tried to get the tower to stand up, but it kept falling and I just thought I couldn’t do it, so I wasn’t believing in myself.

Teacher: It’s really important that you realized you were feeling so frustrated. Sometimes if we have a feeling and we don’t know what it is or how to talk about it, it can be very scary. Mary, how do you think your teamwork would change if Jaylan believed in herself?

Mary: If she just believed in herself and said, “I can do it,” then the tower would have been able to stand up.

Jaylan: Yeah. Next time I will do that.

Both of these exchanges suggest that the children have embraced the difficulties of the challenge without self-defeating mentalities. When Jaylan didn’t believe in herself, a peer reminded her of the value of having self-confidence in order to succeed. Jaylan and Mary were able to reflect on their performance together without punishing each other for their trials during the activity.

Amir had previously shown very low self-esteem throughout the year. He had said things like “I’m the dumbest one in class” and “I’m not as good as the people on my team.” Reminding his team that the challenge was not about competition shows remarkable growth and a positive change in Amir’s belief about himself and about how success can be measured.

One of the most interesting parts of this activity for me was that my intentional choice not to mention the words competition, win, or lose during my lesson—the only change I made to the facilitation of the Marshmallow Challenge model—seems to have helped students appreciate each others’ strengths, efforts, and contributions as team members. In the long run, these shifts may have improved morale and sportspersonship during group activities.

Peacemaking in Action

The following two transcripts, chosen from several recordings and interviews that I did, provide a sense of how my students were embracing peace.

The first is a transcription of a peace corner conversation between Darian and Robert working out an issue from the basketball court.

Robert: I don’t like when you say, “Oh, my gosh,” because remember when we were playing outside and Ivan passed the ball to me and you said, “Oh, my gosh”? Um, he did the right thing because he shot and gave it to somebody.

Darian: I didn’t like when you were mad at me when I didn’t give you the ball and I gave it to somebody else.

Robert: Well, I didn’t like when you said, “Oh, my gosh.” It makes my feelings hurt. Can you try to not say that again? But next time if I get the ball I’ll give it to you, okay?

Darian: Next time if I don’t give the ball and the ball goes off the rim, just try to get the rebound!

Robert: Okay. Next time maybe we could ask coach Andy if we can play change [a turn- taking adaptation to a standard basketball game] so you don’t have to push me— remember when I had the ball and you pushed me and it came out of my hands? So try not to do that again, okay?

Darian: Okay. [Robert reaches his hand out for a handshake. Darian puts his hand out and smiles while they shake hands.]

The second excerpt comes from an interview with Darian and Robert after the session in the peace corner.

Teacher: What do you think about the peace corner?

Robert: People go in the peace corner and do their problems. So we can talk and we can say nice words, so we don’t have to get angry.

Teacher: What about you, Darian?

Darian: I like the peace corner because we can come and talk about our feelings so we won’t be sad.

The recordings and conversations convinced me that my students were learning to talk with each other. My next step was to help them work interactively and thoughtfully on interesting classroom problems. For this step, I chose the Marshmallow Challenge.

Conclusion

For me, this experience suggests the enormous potential of developing children’s communication skills to support social and emotional well-being in early childhood classrooms. I learned how important it is to create an environment in which children can be successful as problem solvers. Giving my students words to help them describe their feelings was critical to making this happen, but so, too, was implementing the strategies that I had seen in my first placement and heard about from my peers.

After I completed this project, the principal said that the model of peacemaking we had developed in the kindergarten was so successful that the school would begin implementing it on the playground the following school year. I, of course, cannot take full credit, because I was recreating a system inspired by another teacher in another school, but knowing that peacemaking would carry on is really exciting. I now see that even seemingly small interventions that work for students and teachers can catch on little by little and lead to a widespread change in the mind-sets of teachers, schools, administrators, and policy makers.

I know it isn’t easy for teachers to engineer a set of activities like this—particularly in the highly stressful, underresourced environments that so many encounter now—but studying our work and sharing with others means that we are no longer alone in our classrooms. We can be a community of learners studying how to create more peaceful and inclusive classrooms.

References

Edwards, C., L. Gandini, & G. Forman, eds. 2011. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. 3rd ed. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Gardner, H. [1991] 2011. The Unschooled Mind: How Children Think and How Schools Should Teach. 20th Anniversary ed. New York: Basic Books.

Jackson, P.W. 1968. Life in Classrooms. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Kohn, A. 1987. “The Case Against Competition.” Working Mother 10 (9): 90–95. www.alfiekohn.org/article/case-competition.

Maslow, A.H. 1943. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review 50 (4) 370–96.

McLeod, S.A. 2016. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.” Simple Psychology. www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html.

Prashnig, B. 2005. “Learning Styles vs. Multiple Intelligences (MI): Two Concepts for Enhancing Learning and Teaching.” Teaching Expertise

9: 8–9. www.creativelearningcentre.com/downloads/lsvsmitex9_p8_9.pdf.

Tomlinson, C.A., & J. McTighe. 2006. Integrating Differentiated Instruction and Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Wujec, T. 2015. “Marshmallow Challenge.” www.tomwujec.com/design-projects/marshmallow-challenge.

Voices of Practitioners is a vehicle for publishing teacher research.

Look for an upcoming special online issue of Voices honoring Gail Perry, the late Voices editor. Many thanks to Voices coeditor Barbara Henderson, executive editors Frances Rust, Andy Stremmel, and Ben Mardell, and the Editorial Advisory Board for their continued support of Voices and teacher research.

Holly Dixon, MSEd, is a first grade teacher at Inquiry Charter School in West Philadelphia. Since 2008 Holly has taught in early childhood classrooms focused on social and emotional well- being, outdoor leadership, and elementary after-school programs.