Transnational Lives of Asian Immigrant Children in Multicultural Picture Books

You are here

Ms. Park: What do you think will happen next?

Hyunho: Juno is going to write a letter to his 할머니. (Juno is going to write a letter to his grandmother.)

Simon: Grandma in 한국! (Grandma in South Korea!)

Dongho: South Korea, not North Korea.

Eunjin: My 엄마 always calls my grandma. My grandma sends presents to me and my brother. (My mom always calls my grandma. My grandma sends presents to me and my brother.)

Hanbyul: 할머니가 편지도 줬어? (Did she send you a letter?)

Eunjin: No.

This opening conversation was a snapshot of young Korean immigrant children in a Korean class at a community-based heritage language school in North Carolina. They were discussing a picture book called Dear Juno, by Soyoung Pak. While the primary-grade children had different migration histories and varied levels of Korean language proficiency and cultural understanding, each child made a meaningful connection to Juno, the main character, and the story about the letters exchanged between Juno and his grandmother in South Korea. When Ms. Park asked the class to predict what will happen after Juno receives a letter from his grandmother, the children applied their existing knowledge, multilingual repertoire, and transnational expertise as they co-constructed the story ending and predicted that Juno will write back to his 할머니 (grandmother) in 한국 (South Korea). Eunjin made a personal connection related to gift-giving. These children then continued actively discussing what it means to have families abroad and how they communicate with them through writing letters, talking on the phone, connecting online, and visiting the countries where their families live.

Transnational Experiences of Immigrant Children

Young immigrant children with one or both parents who were born in a country outside the United States typically live transnationally. Transnationalism refers to the “sustained and meaningful flows of people, money, labor, goods, information, advice, care, and love” (Sánchez 2007, 493), often spanning geographic borders and multiple cultural contexts. These include, but are not limited to, visiting home countries, attending religious rituals, participating in phone conversations, and exchanging emails, texts, and videos with relatives abroad (Vertovec 2004; Lam & Rosario-Ramos 2009; Gardner 2012). Greater access to technology and international travel has created a rich array of transnational opportunities for immigrant children.

Transnational practices shape young immigrant children’s everyday lives in many ways, particularly in their understanding of languages, cultures, and the world around them (Orellana 2016; Kleyn 2017; Kwon 2017). A study by Jungmin Kwon and colleagues published in 2019, for example, demonstrated how a Cantonese-English emergent bilingual child shared her transnational and bilingual expertise through creating artifacts such as multimodal drawings, writings, and photographs. She also enriched her peers’ and teachers’ understanding of bilingualism and challenged their assumptions about the Chinese language by surfacing her bilingual identity and transnational expertise. Given the increasing number of immigrant children and families who forge multilayered relationships between their societies of origin and settlement (Basch, Schiller, & Blanc 1994), it is important that educators and researchers pay attention to immigrant children’s experiences and honor and actively incorporate their transnational expertise into early learning settings (Sun & Kwon 2020).

Picture books are powerful tools that can promote young children’s early literacy and language skills as well as their awareness and understanding of different social identities.

While the transnational population in school and society in the United States is increasing rapidly, few have considered the transnational lives of immigrant children and youth from an asset-based perspective until more recently (Falicov 2005; Sánchez 2007; Sánchez & Kasun 2012; Kwon 2021). Teachers and schools often may not encourage children’s transnational engagements and may undervalue the meaningful stories and knowledge that these children bring to classrooms (Skerrett 2015; Orellana 2016). Scant attention has been paid to the ways educators can build upon immigrant children’s transnational experiences and knowledge. The literature that does exist tends to focus on the border-crossing experiences of immigrant children from Latin America; far less is known about the experiences of immigrant children and their families from East Asian cultures.

As researchers and educators from China and Korea, we have the nuanced linguistic and cultural understanding of East Asian context. As such, in this article, we explore how East Asian immigrant children’s transnational experiences are portrayed in contemporary multicultural picture books. We also discuss ways for educators to use these resources to enhance children’s literacy learning while simultaneously offering an inclusive space for discussion about multilingualism, mobility, and cultural diversity.

Representations of Immigrant Children in Picture Books

Picture books are powerful tools that can promote young children’s early literacy and language skills as well as their awareness and understanding of different social identities (Bishop 1990; Wee, Park, & Choi 2015). When appropriately selected and used, texts about linguistically and culturally diverse children and families can support instruction and enhance children’s intercultural awareness of diversity and inclusion (Klefstad & Martinez 2013; Wee, Park, & Choi 2015). Yet despite their great potential, only a small number of picture books are about people of color and migration populations.

Picture books are powerful tools that can promote young children’s early literacy and language skills as well as their awareness and understanding of different social identities (Bishop 1990; Wee, Park, & Choi 2015). When appropriately selected and used, texts about linguistically and culturally diverse children and families can support instruction and enhance children’s intercultural awareness of diversity and inclusion (Klefstad & Martinez 2013; Wee, Park, & Choi 2015). Yet despite their great potential, only a small number of picture books are about people of color and migration populations.

This is particularly true regarding Asian immigrant children and their experiences (Yamate 1997). Yi (2014) analyzed Asian immigrant children’s picture books and identified the necessity of having more Asian American stories available to children. In an analysis of Korean American picture books, Yi demonstrated common themes, including English acquisition, name selection, language mediation, family separation, and post-immigration experiences. Although these issues are not generalizable to all Asian immigrant children, Yi’s work provides a great entry point for our exploration.

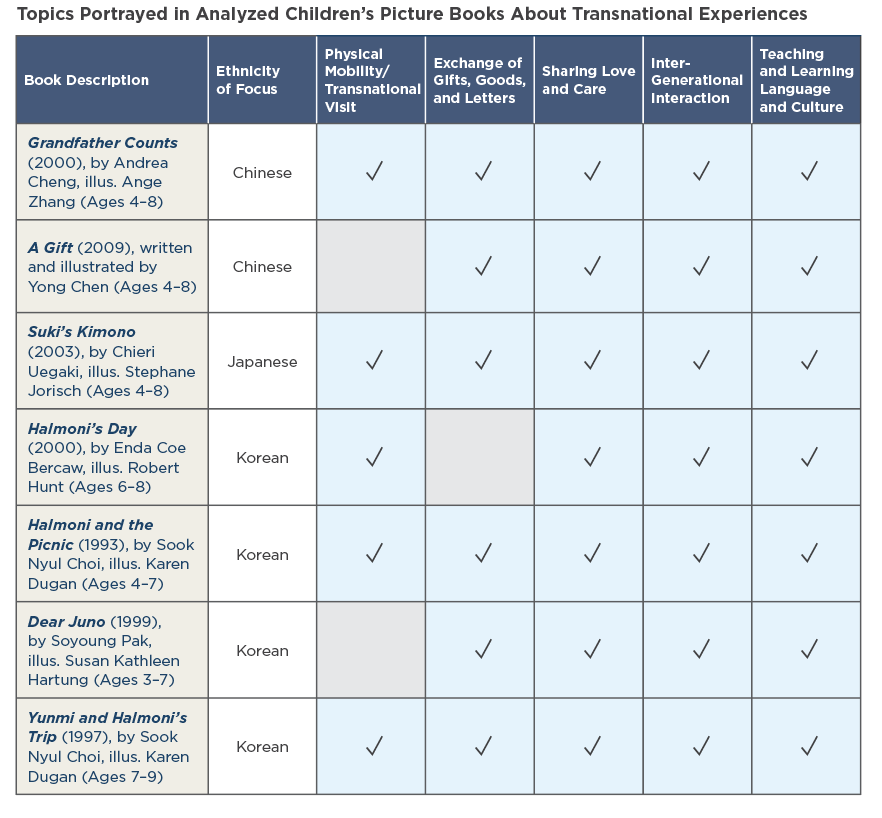

We analyzed seven picture books that depict the transnational lives of immigrant children with parents (one or both) from East Asian countries (see “Topics Portrayed in Analyzed Children’s Picture Books About Transnational Experiences” below). We used the Database of Award-Winning Children’s Literature (DAWCL) and Children’s Picture Book Database at Miami University to identify and locate books to review. We searched for, reviewed, and selected children’s picture books based on specific criteria:

- the portrayal of characters and events of East Asian immigrant families (of which there were substantially fewer than other representations)

- the portrayal of children’s experiences in the context of transnationalism—the flow of people, artifacts, care, and love across countries (Sánchez 2007; Skerrett 2015; Kwon 2021)

Books that only portrayed aspects of cultures (e.g., Chinese New Year or ancient Korean myths) without the mention of transnational experiences were excluded.

After selecting the picture books that met our selection criteria, we closely read the stories and coded the texts and illustrations using qualitative data analysis software. We identified three themes: physical mobility between the United States and home countries; sharing love and care across substantial distances; and bilingual and bicultural learning through family interactions.

Physical Mobility Between the United States and Home Countries

One of the most prevalent practices depicted in the seven books is international travel: either the immigrant child visiting the parents’ home countries or grandparents coming to the United States. Five of the seven stories we analyzed featured physical mobility or transnational visits. These stories illustrate the transnational activities and cultural occasions that children and grandparents engage in during their mobile experiences, such as tourism activities (sightseeing) and attending family events (cultural rituals, meeting relatives). Consistently, storylines describe how the main character develops a more nuanced understanding of heritage language and culture by visiting a parent’s home country or spending time with a grandparent who visits the United States.

Halmoni and the Picnic, by Sook Nyul Choi, tells of Yunmi, a Korean immigrant child who lives in New York City, and the time she spends with her grandmother, who is visiting from Korea. During her grandmother’s stay, Yunmi plays important roles as a cultural mediator and a language broker by teaching her grandmother English expressions and cultural etiquettes. Yunmi also shares about Korean culture with her classmates and the importance of showing respect for the elderly when her grandmother joins her school picnic. Through close interaction with her grandmother, Yunmi becomes motivated to learn about her ethnic culture. She also looks for ways to communicate with her grandmother to overcome the language barrier. In a subsequent book about Yunmi, Yunmi and Halmoni’s Trip, Yunmi travels to Korea with her grandmother to meet her aunts, uncles, and cousins. Yunmi visits several different locations with her cousins, such as the royal palace Kyong Bok Kung and the National Museum. The book shows how Yunmi becomes more aware of the Korean culture as she learns about Korean history.

The physical mobility portrayed in these stories connects to research about immigrant children’s border-crossing experiences and how they learn about their heritage language and culture through these journeys. However, the grandmothers in these stories are stereotypically portrayed wearing hanbok, the Korean traditional dress, and they appear to have passive personalities. While these images can teach children about traditional clothing, they can also perpetuate stereotypes about older generations of Koreans. Moreover, the analyzed books only illustrate the physical mobility between two countries: the United States and the parents’ home country. In reality, immigrant children’s transnational backgrounds are becoming more diversified, and some families maintain connections to more than two countries and cultures (Kwon 2019). Hence, when incorporating these stories, it is important to engage children in a discussion about multiple experiences of identity and belonging.

Sharing Love and Care Across Substantial Distances

All seven picture books display the love and care shared intergenerationally and transnationally. Most highlight border-crossing communication practices where letters and gifts are exchanged, and they include characters thinking about, talking about, and missing family members on the other side of the world. Young readers can learn about sustained connections and relationships with families and friends in distant homelands.

Dear Juno, by Soyoung Pak, depicts how Juno, a young Korean American child, develops his connection with his grandmother in Korea through letters, photographs, and gifts like dried flowers and drawings. Through their correspondence, Juno gradually comes to know more about his grandmother and her daily life. Juno’s border-crossing communication fosters transnational imagination, through which he develops his sense of belonging to Korea, a country he has never visited. The story ends with Juno dreaming about the faraway place where his grandmother lives: “Soon Juno was fast asleep. And when he dreams that night, he dreamed about a faraway place, a village just outside Seoul, where his grandmother whose gray hair sat on top of her head like a powdered doughnut, was sipping her morning tea.” The two last images—the picture of Juno reading the letter from his grandmother and the picture of the grandmother sipping tea—are placed together to show the connection built through the letter exchange.

A similar practice of exchanging a meaningful gift and a letter across countries is depicted in another picture book called A Gift, written and illustrated by Yong Chen. In the story, Amy, a Chinese American child, has never met her extended family in China, but she knows a lot about them because she has received many letters and packages from them. When she opens a box from China, she finds a necklace shaped like a dragon (the symbol of China). The enclosed letter describes how her relatives in China “worked for many days, carving and polishing” the necklace for Amy. As her mother hands the gift to Amy, she says, “It’s a gift from our family” and “Happy New Year!” Amy, proudly wearing the dragon necklace, then offers New Year’s greetings “to my family far away.” Stories such as the one portrayed in A Gift show how the concept of family spans across borders for these transnational immigrant children because they consider the family members in foreign countries, whom they have never met but have communicated with through written letters and artifacts, as part of “our family.”

The stories that depict love and care shared across borders illustrate how close ties with grandparents and other extended family in home countries are important parts of young immigrant children’s lives. Just as Juno engages in multilingual literacies when he writes a letter to his grandmother, immigrant children today use their multilingual knowledge as they communicate transnationally using digital tools, emails, videos, and text messages (Lam & Rosario-Ramos 2009).

Bilingual and Bicultural Learning Through Family Interaction

Along with transnational communication, immigrant children expand their linguistic and cultural repertories through transnational experiences including interactions with family. In fact, a frequently occurring theme in all seven books we analyzed is how immigrant children engage in bilingual and bicultural learning through family interactions despite language barriers.

Grandfather Counts, a story by Andrea Cheng, begins with the illustration of an airport where Helen, a Chinese American girl, excitedly welcomes her grandfather visiting from China. Helen soon realizes how challenging the language barrier between them is, despite her efforts to improve her Chinese with Chinese flash cards and by attending Chinese Sunday school. In Grandfather Counts, the language difference creates a bond as Helen and her grandfather each try to teach their own language and learn another. They teach each other how to speak and write numbers, words, and names. They engage in various language learning activities, such as guessing the meanings of words, copying Chinese characters, and translating for each other. Despite the challenges that stem from language barriers, Helen becomes more motivated to learn her heritage language and culture through interactions with family members from her parents’ home country. Similarly, in Dear Juno, Juno initially finds it challenging to read and understand the letters from his grandmother living in Korea, which are written in Korean. His mother helps by translating the letter into English, so Juno can learn more about his grandmother. He also sends a letter back to her with drawings of himself, his parents, and his friends.

These stories can resonate with many immigrant children who build and maintain connections with their family members in other countries yet have difficulties communicating with them due to language differences. Moreover, the characters’ engagement in multilingual practices–translating, reading nonverbal cues, and altering between multiple languages–can help young readers understand how to draw on their multilingual repertories to mitigate the difficulties in transnational communication.

Teaching with Transnational Picture Books

Immigrant children can better engage in language, literacy, and content learning when teachers incorporate their transnational experiences and linguistic and cultural knowledge into instruction (Jiménez, Smith, & Teague 2009; Souto-Manning 2013). Multicultural picture books can be used to inform educators about the transnational practices that contemporary immigrant children and their families engage in, such as how they communicate with loved ones in other countries through letter writing. These books can also be used to share experiences and knowledge that immigrant children construct through these practices, such as new vocabulary words in their family’s home language.

Multicultural picture books can inform educators about the transnational practices of immigrant children and their families.

These stories also provide teachers with opportunities to better support linguistically and culturally diverse children in their classes whose lives may encompass multiple languages and cultures. While these books are valuable resources to understand the cultural values and practices of transnational children, it is crucial for teachers to recognize the heterogeneity and complexity of transnational children’s experiences. Some books may represent stereotypical images of immigrant families. Therefore, it is important to center children and/or their families’ voices in interpreting these stories and invite them to author their own transnational experiences that may resonate with or differ from portrayals in the available picture books.

Recommended Practices

To select books that are culturally authentic and responsive, educators should consider the following factors when evaluating multicultural narrative picture books (Goodman 1982; Ebe 2011):

-

characteristics of the book, such as

- the ethnicity, gender, age, and language or specific dialect of the characters in the story

- the setting, including the year and context in which the story takes place

- the storylines, including which characters and cultures are included and excluded and how they are portrayed

-

characteristics of the reader, such as

- the children’s familiarity with this type of text or genre

- the reader’s own linguistic and cultural backgrounds

- the children’s migration histories and transnational experiences

Moreover, teachers should actively engage young transnational learners in the book selection. Teachers may also invite children to bring in books and oral stories that they engaged with at home and they feel associated with. It is important to create a space where the children can interpret how these books are connected or disconnected with their experiences. This practice takes children’s voices into account and informs the selection of culturally responsive and sustaining materials that correspond to learners’ dynamic identities in a transnational context (Paris & Alim 2017).

Finally, as a component of a larger project or ongoing theme of study, teachers can use picture books such as Dear Juno and A Gift in whole-group read-aloud activities. These could include engaging children in meaningful discussions about their experiences sharing stories and artifacts with their families and friends in different countries. Teachers also may invite children to engage in multilingual and transnational literacies (Jiménez, Smith, & Teague 2009) by writing letters to people abroad using different languages. Other projects may explore and open up discussions about timely, longstanding, and sensitive issues and events, such as family separation and deportation. For example, From North to South / Del Norte al Sur, by Réné Laínez, is a bilingual book about the close bond between a young boy and his deported mother. Projects like these also offer many opportunities to invite family members into the classroom and position them as multilingual and transnational experts. For example, as described in Halmoni and the Picnic, learning experiences can reaffirm to immigrant families and students that their linguistic and cultural knowledge are assets to school and society.

Conclusion

In this article, we presented how transnational experiences are portrayed in multicultural picture books about immigrant children from East Asian families. As our study and others’ work shows, moving across linguistic and cultural borders can enrich young immigrant children’s lives. The analyzed books also illustrate immigrant children’s and families’ unique experiences, which include the physical mobility between multiple countries, the love and care shared across geographic boundaries, and bilingual and bicultural learning through family interactions.

When appropriately and effectively selected and incorporated, diverse multicultural picture books can be powerful tools in classrooms to create meaningful dialogue about immigrant children’s transnational practices and global connections. In addition to the analyzed stories, a number of children’s books illustrate the transnational experiences of children from backgrounds that are not East Asian. While they were not included in this review, they are still of value and can be incorporated into lessons on transnationalism. Such stories include Hot, Hot Roti for Dada-ji, by Farhana Zia, which tells the story of a child sharing the cultural traditions of his grandfather from India, and Sitti’s Secrets, by Naomi Shihab Nye, which depicts a child’s visit to her grandmother in a small Middle Eastern village.

It is important to acknowledge that these stories and portrayals cannot represent all immigrant children’s experiences. A few of the analyzed picture books provided homogenous and stereotypical descriptions of cultural practices, which may generate and perpetuate stereotypical ideas among young readers about transnational immigrant children. Nonetheless, these picture books provide a solid starting point for generating rich discussion on transnational experiences and global interconnectedness in classrooms. We hope our analysis provides information to help educators shift from viewing immigration as a one-way linear process and pushes them to foster, validate, and celebrate knowledge and experiences that young immigrant children construct from participating in transnational networks.

Further Resources

For further reading and more information about incorporating transnational experiences in the classroom, check out the following resources.

- Social Justice Books’ list of multicultural and social justice books for children, young adults, and educators, with a focus on Asian American experiences

- Millikin University’s list of children’s literature with a focus on Asian/Asian American experiences

- Anti-Bias for Young Children and Ourselves, 2nd edition (2020) by Louise Derman-Sparks and Julie Olsen Edwards, with Catherine M. Goins

- Using Picture Books about Refugees: Fostering Diversity and Social Justice in the Elementary School Classroom by Hillary A. Libnoch and Jackie Ridley, published in Young Children, December 2020

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Basch, L., N.G. Schiller, & C.S. Blanc. 1994. Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States. London: Gordon & Breach.

Bishop, R.S. 1990. “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors.” Perspectives 6 (3): ix–xi.

Ebe, A.E. 2011. “Culturally Relevant Texts and Reading Assessment for English Language Learners. Reading Horizons 50 (3): 193–210.

Falicov, C.J. 2005. “Emotional Transnationalism and Family Identities." Family Process 44 (4): 399–406.

Gardner, K. 2012. “Transnational Migration and the Study of Children: An Introduction." Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (6): 889–912.

Goodman, Y.M. 1982. “Retellings of Literature and the Comprehension Process.” Theory Into Practice: Children’s Literature 21 (4): 301–307.

Jiménez, R.T., P.H. Smith, & B.L. Teague. 2009. “Transnational and Community Literacies for Teachers.” Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 53 (1): 16–26.

Klefstad, J.M., & K.C. Martinez. 2013. “Promoting Young Children’s Cultural Awareness and Appreciation Through Multicultural Books.” Young Children 68 (5): 74–81.

Kleyn, T. 2017. “Centering Transborder Students: Perspectives on Identity, Languaging, and Schooling Between the US and Mexico.” Multicultural Perspectives 19 (2): 76–84.

Kwon, J. 2017. “Immigrant Mothers’ Beliefs and Transnational Strategies for Their Children’s Heritage Language Maintenance.” Language and Education 31 (6): 495–508.

Kwon, J. 2019. "Parent-Child Translanguaging Among Transnational Immigrant Families in Museums." International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1689918

Kwon, J. 2021. "The Circulation of Care in Multilingual and Transnational Children." Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice 69: 99–119.

Kwon, J., M.P. Ghiso, & P. Martínez-Álvarez. 2019. “Showcasing Transnational and Bilingual Expertise: A Case Study of a Cantonese-English Emergent Bilingual Within an After-School Program Centering Latinx Experiences.” Bilingual Research Journal 42 (2): 164–177.

Lam, W.S.E., & E. Rosario-Ramos. 2009. “Multilingual Literacies in Transnational Digitally Mediated Contexts: An Exploratory Study of Immigrant Teens in the United States.” Language and Education 23 (2): 171–190.

Orellana, M.F. 2016. Immigrant Children in Transcultural Spaces: Language, Learning, and Love. New York: Routledge.

Paris, D., & H.S. Alim. 2017. “What Is Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy and Why Does It Matter?” In Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World, eds. H.S. Alim, & D. Paris, 1–21. New York: Teachers College Press.

Sánchez, P., & G.S. Kasun. 2012. “Connecting Transnationalism to the Classroom and to Theories of Immigrant Student Adaptation.” Berkeley Review of Education 3 (1): 71–93.

Sánchez, P. 2007. “Urban Immigrant Students: How Transnationalism Shapes Their World Learning.” The Urban Review 39 (5): 489–517.

Skerrett, A. 2015. Teaching Transnational Youth: Literacy and Education in a Changing World. New York: Teachers College Press.

Souto-Manning, M. 2013. “Preschool Through Primary Grades: Teaching Young Children from Immigrant and Diverse Families.” Young Children 68 (4): 72–80.

Sun, W., & Kwon, J. 2020. Representation of Monoculturalism in Chinese and Korean Heritage Language Textbooks for Immigrant Children. Language, Culture and Curriculum 33 (4): 402–416.

Vertovec, S. 2004. “Migrant Transnationalism and Modes of Transformation.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 970–1001.

Wee, S., S. Park, & J.S. Choi. 2015. “Korean Culture as Portrayed in Young Children’s Picture Books: The Pursuit of Cultural Authenticity.” Children’s Literature in Education 46 (1): 70–87.

Yamate, S.S. 1997. "Asian Pacific American Children's Literature: Expanding Perceptions about Who Americans Are" in Using Multiethnic Literature in the K–8 Classroom (95–128). V. Harris, ed. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon.

Yi, J.H. 2014. “‘My Heart Beats in Two Places’: Immigration Stories in Korean-American Picture Books.” Children’s Literature in Education 45 (2): 129–144.

Jungmin Kwon, EdD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Teacher Education at Michigan State University. Her research focuses on language and literacy experiences of immigrant children and families in the transnational context of migration. Her work has been published in journals such as International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, Bilingual Research Journal, and Language and Education. [email protected]

Wenyang Sun, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Education, Culture & Society at the University of Utah. Her research interests include bilingual education, heritage language maintenance, Asian American studies, and critical multicultural education. Her work has been published in journals such as Language, Culture and Curriculum and Journal of Language, Identity & Education. [email protected]