Support You Can See (and Feel): Teaching Children with Autism

You are here

Accreditation Standard 3: Teaching

Teachers who purposefully use multiple instructional approaches optimize children’s opportunities for learning. Children arrive in preschool with different backgrounds, interests, experiences, and abilities. By considering these differences, teachers are better able to meet each child’s needs and help all children learn. This article supports standard 3 by sharing instructional supports for children with autism spectrum disorder.

Michael is 3 years old and was recently diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). His mother became worried when he was 18 months old because he wasn't talking, but the pediatrician told her not to worry—boys talk late. However, the more time she and Michael spent with other families, the more her concerns grew. In particular, when they went to their neighborhood play group for toddlers, Michael's mother noticed that Michael seemed noticeably different from the other children his age.

By age 3, the pediatrician shared Michael's mother's concerns and suggested she contact her local Child Find department. Michael's mother had never heard of Child Find, so she was surprised to learn that this service is available across the country. It's required by federal law that all public school districts have processes for identifying, and then offering services to, children who have disabilities. If only she had known about Child Find when Michael was just a year old!

Through Child Find, Michael was diagnosed and placed in an integrated preschool classroom that had a mix of children with and without disabilities. Although Michael said only a few words to communicte, he could sing entire songs and recite lines from TV shows and movies.

The first few weeks in preschool presented challenges. Michael didn't understand what he was supposed to be doing, where in the classroom he was supposed to be, or how to do the activities the other children were doing. As his teacher saw how much trouble Michael was having, she began to develop a number of visual supports she thought would make it easier for Michael to participate in the life of the classroom.

What are visual supports?

Children with ASD usually have difficulty understanding language that they hear. When they listen to others speaking, they may not be able to keep up: by the time they understand the beginning of the first sentence, the speaker may be on to the fifth sentence. A child with ASD may be trying to listen but still miss most of what is being said.

In contrast, many children with ASD have strengths in processing information visually and in thinking spatially. In the classroom, communicating visually can make a big difference. (This is not to say that verbal communication should stop—children with ASD still need opportunities to develop their language skills.) Visual supports come in many forms: pictures, objects, gestures, and text (once children can read). Images found online, labels from packaging, pictures in catalogs, or software developed specifically for children with ASD are all possible sources of visual supports. Basically, anything informative that children with ASD can see may be considered a visual support.

What Is Autism?

Autism, or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a developmental disability that can generally be diagnosed between 18 months and 3 years of age. Indicators that an evaluation should be done include social interaction and communication differences like little eye contact, lack of shared attention and enjoyment, and an absence of interest in playing with other children. Some children with ASD may be nonverbal, while others may talk in scripted language or echo what they have just heard. Children with ASD may have very strong interests in one particular toy or type of toy (Thomas the Tank Engine, dinosaurs), or they may use toys differently than other children (spinning the wheels on a car with their fingers for long periods of time). Small changes in the environment may make them very upset. ASD has been increasing rapidly, with a current prevalence rate of 1:59. The ratio of boys to girls diagnosed with ASD is 4.5:1.

Using visual supports: Six strategies

1. Tell a child where to sit or stand. Placing markers on the floor to show where to stand when lining up or having a marker on the table or chair showing where to sit lets children with ASD know where they are supposed to be. Carpet squares or classroom rugs with defined seating areas serve the same purpose. You can also tape a line in hallways to help direct children.

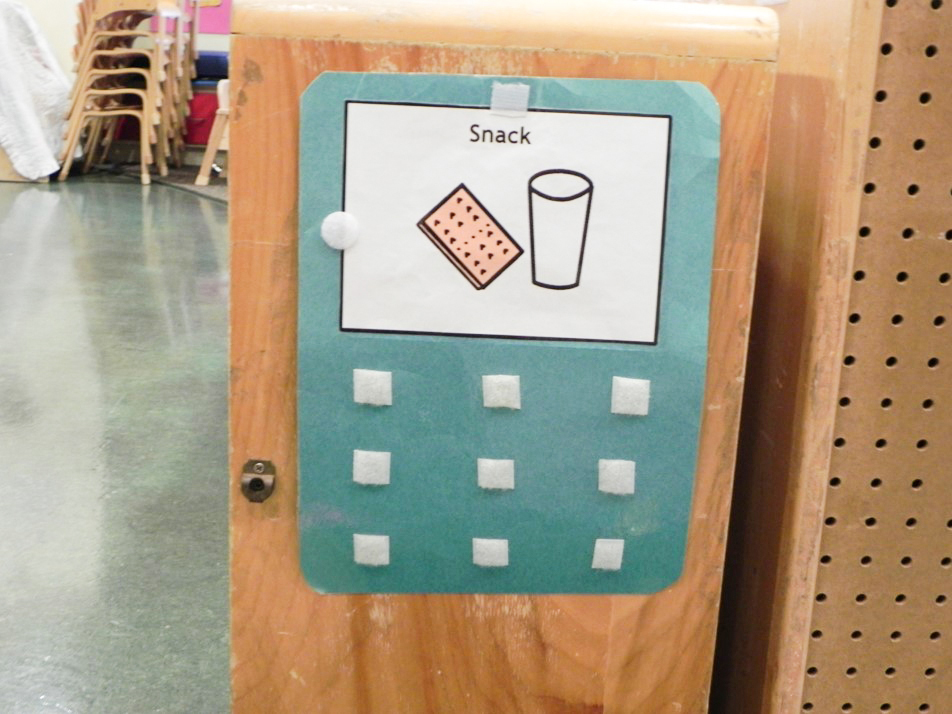

2. Show the schedule of classroom activities. Many teachers make a picture-based schedule of the day’s activities and post it where all of the children can easily check it throughout the day. For children with ASD, it may be helpful to have their own individual schedules that they can manipulate. Providing one picture for each activity and lining them up vertically make it easier for many children with ASD to know what’s happening throughout the day.

Some children do better if they carry the picture representing an activity with them to the activity area and check in. Other children prefer to turn the picture over and then make their way to the appropriate area.

If you have a child who needs even more support, you can make detailed schedules for what will happen within each activity. For circle time, you might make a short schedule showing a song, read aloud, and any other activities you have planned. These schedules may also depict tasks to be accomplished, such as playing hopscotch or walking and crawling like different animals during gross motor time.

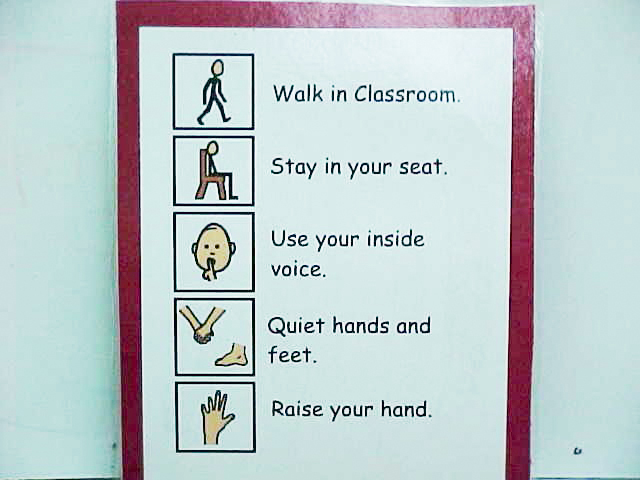

3. Support understanding what you are saying. Often, when teachers give verbal directions, children with ASD may not respond. You might feel that a child is being willfully disobedient, but the child might not understand you. Having pictures to accompany your verbal directions can help. If a child with ASD appears distressed, try using a visual guide instead of a verbal one (since hearing even more hard-to-understand words may increase the child’s frustration). To support children with ASD in group activities, you may find it helpful to show a large picture of “sit down” or “be quiet,” or to have a set of pictures on a lanyard you can show to individual children when necessary.

4. Help a child develop self-regulation. To foster children’s social and emotional development, teachers often share—and have children practice—strategies for calming down, like breathing deeply or going to a cozy nook in the room. For children with ASD, visual explanations and reminders of these strategies can help them self-regulate, especially when they are beginning to become upset. Showing a picture of a person taking a deep breath or squeezing his or her hands together provides a model that is easier to understand than a verbal direction.

Self-regulation skills for positive emotions (like being excited) need to be taught too. For example, a five-point scale for voice level can be represented visually so all the children know when they are using an outside voice or an inside one.

5. Foster independence. Visually presenting the steps to complete a task encourages children to be independent. For example, you could list the steps for brushing your teeth, washing your hands, and using the bathroom; select a picture to represent each step; and post these guides in the appropriate areas of the bathroom. Functional routines, like hanging up coats, can also be represented with pictures.

Another use of visual supports is to put photos of toys and other classroom materials on the shelves where they belong so children can clean up without assistance, enabling children to be independent in this classroom task. Sometimes, taking the adult who is providing verbal directions out of the situation results in the child with ASD being more willing and able to follow directions.

6. Expand the use of expressive language. Children with ASD often have difficulty expressing themselves verbally. Providing pictures that support communication—such as single pictures for children who are beginning to communicate either verbally or nonverbally and language expansion boards for more skilled children—will encourage them to use words expressively, either with or without speech. Handing a picture to a conversational partner or pointing to a picture to show something to a teacher or peer serves as intentional communication for a child who is nonverbal. This boosts understanding between the teacher and the child. In addition, increasing the child’s ability to communicate often decreases challenging behavior.

Similarly, giving children choices often reduces inappropriate behavior—and giving children with ASD visuals for making choices can be very helpful. For children who are not able to understand two-dimensional pictures, the actual objects can be presented. (While this is not always feasible, it can be done at key times, like when helping a child decide whether to go to the block center or to the light table.)

Revisiting Michael’s classroom

The first thing Michael’s teacher did to help him adjust to the classroom was to create an individual schedule for him by velcroing a picture of each activity to a long, vertical piece of felt. His schedule ended with a photo of his mother, which was comforting to him and also reassured him that she would pick him up at the end of the day.

The schedule made it easier for Michael to navigate the classroom throughout the day’s activities. As part of his transition between activities, he carried the appropriate picture and checked in to the area he was assigned to. Since Michael could see when the end of the day was coming, he stopped asking for his mother throughout the day. Michael’s teacher also created visuals to show the tasks within each activity and to show the steps for functional routines, like washing hands before snack time.

After working with Michael for a couple of weeks to understand his current communication skills and to get to know his interests, Michael’s teacher developed a communication board for him to ask for preferred items and to express “no” when he didn’t want something. She labeled his cubby, his chair at the group table, his work area, and his spot on the carpet so that he could rely on visual instead of verbal reminders. All of these visual supports helped Michael adjust to his new classroom and enabled him to participate in each day’s activities without feeling stressed or overwhelmed by his teacher’s verbal directions.

Selected Accreditation Assessment Items Related to Teaching Children with Autism

3A.3 Show or describe two ways in which teaching staff, program staff, and/or consultants work as a team to implement individualized plans for children. Such plans may include any Individualized Family Service Plans (IFSPs) and Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).

3B.2 When a child’s ongoing challenging behavior must be addressed, show a written policy including these steps:

- Assess the function of the behavior

- Work with families and professionals to develop an individualized plan to address the behavior

- Include positive behavior support strategies as part of the plan

3E.7 Teachers sometimes customize learning experiences, based on their knowledge of the children’s social relationships.

Photographs: top of article © Getty Images; images within article, courtesy of the author.

Susan Kabot is the executive director of the Autism Institute at the Mailman Segal Center for Human Development at Nova Southeastern University, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. For more information, visit https://msc.nova.edu/autism-institute/index.html.